In 2016 — 2016! — my colleague, Mary Soliday, and I published an article called “Rethinking Regulation in the Age of the Literacy Machine,” focused on SF State students’ perceptions about writing. Our motivation was a long-held curiosity about students who describe school writing as robotic, requiring them to follow a formula, address topics chosen by someone else, perform and conform to genre constraints and requirements. Writing, for these students, was as a mechanical exercise in navigating a blizzard of rules, mandates, and external expectations.

Mary and I used the phrase “literacy machine” as a shorthand for these mechanical, formula-driven approaches to writing.

Now that we have an actual literacy machine, I have been thinking again about students’ perceptions about writing. In my first-year writing classes, we discuss voice, linguistic justice, writing and identity. We’ve also begun to wrestle with the implications of GenAI. Here are some themes that have emerged (student quotes shared with permission).

Synthetic Writing

Students tell me that AI outputs are boring to read and even offensive. If they are fooled by an AI-generated draft, they feel “betrayed,” “disgusted,” and “like my time has been wasted.” They believe AI output appears “too perfect” — too formulaic and structured, and hence lacking in authenticity, and not worth their time.

BUT, they also think that, for these reasons, synthetic writing would be useful for some types of school writing, which in their view are also formulaic and inauthentic.

The kind of writing that Chat does, it’s what our teachers try to get us to do.

It’s like five paragraph essays, and perfect paragraph structures that don’t have any personality, which we were taught in high school. How is this different?

It borrows from other authors, but we do too. It does what school has trained us to do. Like write a perfectly formatted essay that is based on some random people’s ideas.

These perceptions give voice to John Warner’s point, that automated writing tools will only replace the kind of writing that no one valued anyway. Time to up our game when it comes to the types of writing we assign, and the ways we communicate the purpose of our assignments (more on this below).

Trust

When shown the biases in AI, students are disturbed and disgusted. But they also point out that the tools and platforms we routinely use are all biased (they are not wrong). They take bias as a fact of life, and either work around it or shrug it off.

Everything has biased results. You have to assume its fake.

AI is like searching the internet. It’s faster than google. Google will give you a lot of biased links if you don’t know what question to ask.

If you trust google you can trust this. It’s no more worse than anything else.

You can’t trust anything online, so if you’re going to look online, you may as well use the AI overview because it’s faster than reading through a lot of links that might be fake anyway.

I wouldn’t trust it, but I don’t trust most things online because there is a lot of manipulation and toxic content. You have to be careful of everything.

Countering these views is tricky: we want students to be skeptical. But some information researchers warn that the goal of misinformation isn’t just to get people to believe something that’s false; it’s to get people to lose trust in systems of knowledge altogether. I worry that AI will speed up this problem. When students shrug at my lessons (here and here) showing the biases that plague AI outputs — arguing that “everything is biased anyway” — I worry that we’re seeing them give up on the work of discerning true from false. That work has become more and more impossible, with GenAI. As Jennifer Sano-Franchini has recently written:

What is going to happen to trust in written information and our ability to engage in good faith dialogue when synthetic text is seemingly everywhere? How will this exacerbate the problems of disinformation and misinformation…? How much more anxious and exhausted will we be when there is even more inaccurate, meaningless synthetic text to wade through?

As a quick illustration: this was in my news feed a few days ago:

Worth

Students draw a line between writing they care about and writing that, in their view, already feels like a mechanistic performance (write, submit, gain Canvas points). GenAI is good for the latter.

It works well for writing that doesn’t require emotion, like research papers.

It makes a lot of homework and writing assignments a lot easier, especially for things where the teacher isn’t looking for your ideas.

I would not care if people use it for homework, but I would feel betrayed if I knew that someone used AI to write an essay we read in class. I want to hear an actual person’s views.

If you’ve already learned the material you’re writing about, AI can help, but you shouldn’t let it influence your thinking.

If it’s just for a discussion post for homework points, it could probably help save you time. A lot of times, you’re not putting your real opinion in the post anyway.

If you’re wondering how we remedy this problem — how we address students’ sense that school writing is merely busywork — I recommend the TILT framework, which asks us to make the purpose and value of every assignment maximally transparent to students. For me, this means more than just writing the purpose or learning goal at the top of the assignment. I have to partner with students to engage them about the assignment’s purpose and parameters. I have to invite them into a conversation about the why behind steps in my assignments. Creating this kind of buy-in is an increasingly-recommended way to make your assignments at least somewhat “AI-resistant.”

Equity

Students feel that AI text generators level the playing field, and eliminate linguistic discrimination.

I never get my ideas across in English because it’s like a lot of mistakes and it doesn’t flow. You get judged as a bad writer. For people like that, this would help because the audience would not focus on my grammar mistakes.

It will make everybody seem like they know how to structure their sentences without mistakes so that will give them more of a chance to get a good grade or apply for a job.

It gives me a shot at making people see my ideas. I’m judged as a bad writer no one ever hears my ideas. Now maybe they will.

I’m not yet a capital R refuser when it comes to AI, partly because of the point my students make here. Like them, I am excited by the possibility that AI may eliminate the use of writing as a gatekeeper, and that it might empower students, allowing them access to high-level literacy practices, giving them new opportunities to make their voices heard.

At the same time, I worry that we’re attacking this problem from the wrong end, using AI to erase linguistic diversity, rather than working to change the systems that privilege standard (white) English over all else. As Sano-Franchini, Megan McIntyre, and Maggie Fernandez write, “Writing studies as a discipline stands against linguistic homogenization, which is accelerated and advanced by GenAI.” Accessibility, yes; technologically-engineered homogenization and erasure, no. Threading that needle won’t be easy; we have our work cut out for us.

Loss

Many students share our skepticism about the value and worth of AI tools. They use them, yes, but they don’t necessarily like where this is all headed, and they worry about the effects on their learning, on their writing, and on the future.

What’s its purpose? Why did they make this?

This will create more echo chambers. Like now you can only read the perspectives of people you want to hear. This will make it easy to write from the perspective you want. But now the algorithm picks what you read, and AI decides what you’ll write.

I don’t want to use it because I don’t want to become reliant on it and will never be able to function without it. But I also like saving time and effort, so I think it’s going to be a hard struggle for people to avoid it.

I think it's sad that our kids probably won’t be able to tell the difference between writing from a human and writing from a bot.

I don’t think anything it produces can be considered original. If it’s just guessing at the next most likely word, how is that original?

Writing is a process. That’s where I do all my thinking. I don’t think we should let the bot write our first draft.

It overrides me. It makes it harder for me to think of my own ideas.

This will be really bad for younger kids.

Where does this leave us?

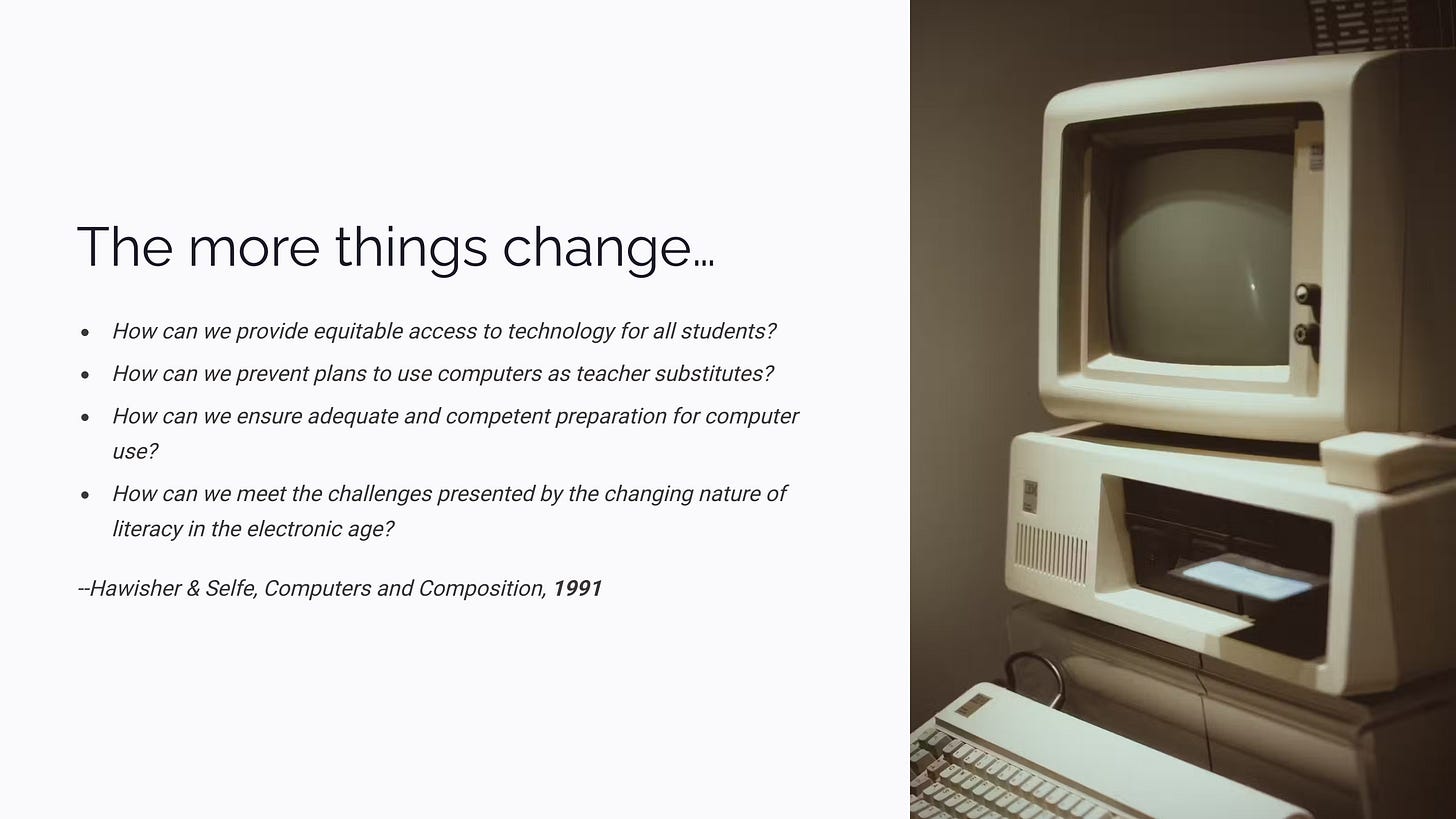

Maybe not too far from where we’ve always been. I have doubled down on my practice of partnering with students about their writing needs, practices, and processes. I center linguistic diversity and celebrate students’ voices. I teach them about the systemic racism and classism behind efforts to police and standardize their writing, in school and via AI writing technologies. I use all kinds of tools and scaffolds to make learning accessible, and I engage them in critiques of tools that don’t reflect our values or that abrogate their rights to their own language. Same as it ever was? To answer that, I’ll leave you with these questions, from 1991!