What's in a name? The Politics of "AI"

by Jennifer Trainor

I read this quirky Scientific American article the other day on the relationship between science fiction and today’s tech billionaires. The author argues that techno-optimists and maximalists have taken the wrong lessons from the science fiction they consumed as kids. It’s a fun read, but one quote stuck with me, from Canadian science-fiction novelist Karl Schroeder: “every technology comes with an implied political agenda.”

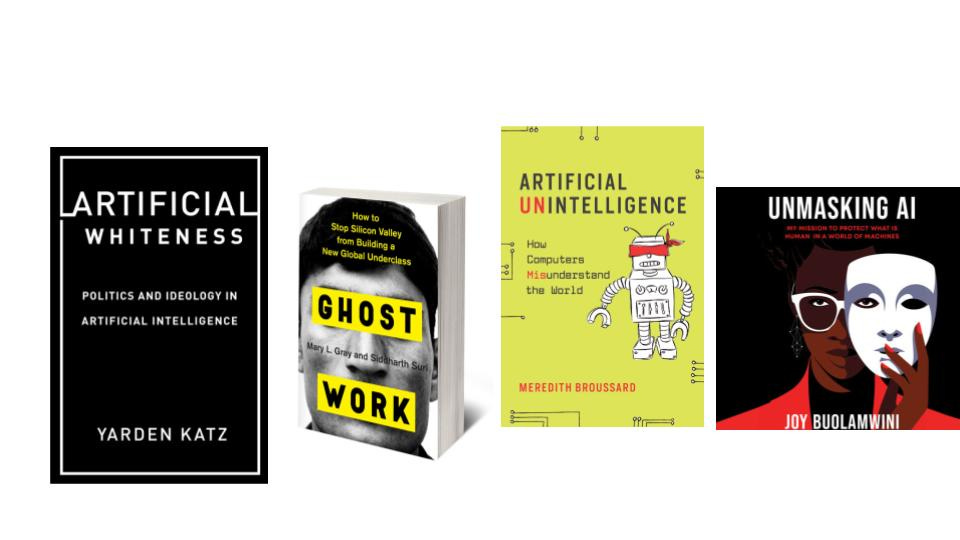

I’m interested in excavating this implied agenda, when it comes to “Gen AI.” The Critical AI movement provides a good start. Aimed at unmasking the negative social consequences of AI technology, Critical AI scholars highlight how these tools promote stereotypes and bias; increase misinformation; degrade the environment and create massive labor exploitation. There are too many good articles to list, but here are a few recommendations, if you are new to the Critical AI movement:

Thinking about Schroeder’s point, that all technology has an implied political agenda, helped me solidify a critique I’ve wanted to make for a while about the words behind what is now a completely ubiquitous and taken-for-granted acronym: AI. It’s always seemed strange to me that in our use of this acronym, we tend to forget about the first word (artificial) and double-down on the second.

Imagine the marketing issues that would arise if we reversed that — if for example, AI companies focused on “artificial” in their marketing: “Artificial medical advice.” “Artificial research support.” “Artificial problem-solving.” “Artificial writing.” “Artificial podcasts and video.” Doesn’t sell quite as well, does it?

But “intelligence” is a hotter commodity, an easy sell. Intelligence — a thinking, reasoning, comprehending, human-outpacing genAI super-being — is apparently marketing gold. One of the first essays I read about LLMs was by Kyle Chayka in The New Yorker. He reviewed Writer, an AI start-up that produces content in the voice of a particular author, brand, or institution. Writer even promises to provide “automated insight extraction.” “Insight extraction” is one way to define “intelligence” when it comes to AI. “Extraction” means to remove by force, and the passive construction obscures answers to questions such as: whose insights are being extracted? by what or whom?

It’s actually hard to think about a definition of the word “intelligence” that doesn’t involve invidious distinctions among people, sorting and classifying them in ways that create winners and losers, or that justify a system of winners and losers (“intelligence” and meritocracy go hand-in-hand, but meritocracy too, has a dark side). It’s hard to separate “intelligence” from elitism and ableism. And it’s imperative that we don’t ignore the historic relationship between concepts of “intelligence” and racism. Indeed, even a quick Wikipedia scan is enough to suggest how much trouble we’re in, as we embrace technologies whose very name associates so deeply with racism.

If you’re interested in reading more, I recommend the LA Review of Books “Legacies of Eugenics” series, especially this barn-burner of an essay by Ruha Benjamin.

Here’s Benjamin: “Smartness in this sense hearkens back to the eugenic underpinnings of both artificial and organic intelligence and its primary directive to categorize and rank humans, eradicating those deemed worthless while propagating those judged worthy.”

A recent conversation with Zainab Agha, assistant professor in Computer Science at SF State helped me think about how tech design choices instantiate the implied politics of technology. Zainab is an expert on human-computer interaction and on tech safety for adolescents (check out her scholarship here). She and I spoke recently about safety in tech, and the need to question AI design choices.

Heavy anthropomorphism is one design choice that we might question. Examples abound, but this one came across my desk a few weeks ago: “Mistral,” an AI-powered document “reader.” According to their website, Mistral “understands,” “comprehends,” and is “natively multilingual.” Thinking about Chayka again: what if Writer had been designed as a tool to support the development of human insight instead of anthropomorphized as a sentient being? Perhaps the tool could be designed as a question generator to help you brainstorm, or as a search engine that quickly creates a greatest-hits list of similar human-generated insights on your topic (like a Google Scholar search, but better)? I know there are some AI tools like that out there, but they are overshadowed by “intelligent” bots that promise to do the work of thinking for you.

Underwhelming and hard-to-find warning labels is another design choice we should question. Zainab, like Benjamin, is very concerned about AI bias and discrimination. She and her students have zeroed in on the design features AI companies are using to mitigate such risks. These features, so far, are poorly conceptualized and much too invisible to provide any kind of guardrail or safety. As Zainab points out, the only warning label on these tools so far is a small disclaimer: “AI is experimental” on Google’s AI overviews, or the laughably understated “Chat GPT can make mistakes. Check important info” in eight point font at the bottom of OpenAI’s Chat GPT screen.

Can we do better? Zainab and her CS students are trying. In her classes, students take a critical lens to the design and underlying politics of technology, and are working together to create better safety protocols and guardrails. Renaming this technology would be my first choice in a redesign challenge. I like names that highlight the artificial in outputs and that abandon “intelligence,” emphasizing instead that this technology provides tools for humans. I’m eager to hear your critiques of these tools. Leave a comment! If you’re working on AI issues with your students, consider presenting at SFSU CEETL’s second annual AI and Teaching Symposium, “Embracing and Resisting AI” on May 2.